Uveitis

Uveitis is a general term describing a group of inflammatory diseases that produces swelling and destroys eye tissues. These diseases can slightly reduce vision or lead to severe vision loss.

The term "uveitis" is used because the diseases often affect a part of the eye called the uvea. Nevertheless, uveitis is not limited to the uvea. These diseases also affect the lens, retina, optic nerve, and vitreous, producing reduced vision or blindness.

Uveitis may be caused by problems or diseases occurring in the eye or it can be part of an inflammatory disease affecting other parts of the body.

It can happen at all ages and primarily affects people between 20 – 60 years old.

Uveitis can last for a short (acute) or a long (chronic) time. The severest forms of uveitis reoccur many times.

Eye care professionals may describe the disease more specifically as:

- Anterior uveitis

- Intermediate uveitis

- Posterior uveitis

- Panuveitis uveitis

Eye care professionals may also describe the disease as infectious or noninfectious uveitis.

What is the Uvea and What Parts of the Eye are Most Affected by Uveitis?

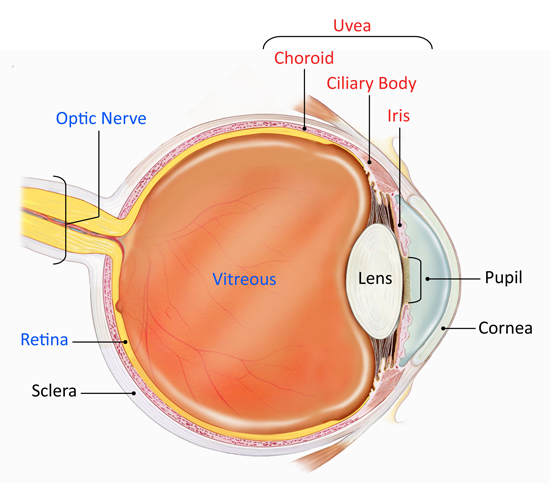

The uvea is the middle layer of the eye which contains much of the eye's blood vessels (see diagram). This is one way that inflammatory cells can enter the eye. Located between the sclera, the eye's white outer coat, and the inner layer of the eye, called the retina, the uvea consists of the iris, ciliary body, and choroid:

Iris: The colored circle at the front of the eye. It defines eye color, secretes nutrients to keep the lens healthy, and controls the amount of light that enters the eye by adjusting the size of the pupil.

Ciliary Body: It is located between the iris and the choroid. It helps the eye focus by controlling the shape of the lens and it provides nutrients to keep the lens healthy.

Choroid: A thin, spongy network of blood vessels, which primarily provides nutrients to the retina.

Uveitis disrupts vision by primarily causing problems with the lens, retina, optic nerve, and vitreous (see diagram):

Uveitis

Lens: Transparent tissue that allows light into the eye.

Retina: The layer of cells on the back, inside part of the eye that converts light into electrical signals sent to the brain.

Optic Nerve: A bundle of nerve fibers that transmits electrical signals from the retina to the brain.

Vitreous: The fluid filled space inside the eye.

What Causes Uveitis?

Uveitis is caused by inflammatory responses inside the eye.

Inflammation is the body's natural response to tissue damage, germs, or toxins. It produces swelling, redness, heat, and destroys tissues as certain white blood cells rush to the affected part of the body to contain or eliminate the insult.

Uveitis may be caused by:

- An attack from the body's own immune system (autoimmunity).

- Infections or tumors occurring within the eye or in other parts of the body.

- Bruises to the eye.

- Toxins that may penetrate the eye.

The disease will cause symptoms, such as decreased vision, pain, light sensitivity, and increased floaters. In many cases the cause is unknown.

Uveitis is usually classified by where it occurs in the eye.

What is Anterior Uveitis?

Anterior uveitis occurs in the front of the eye. It is the most common form of uveitis, predominantly occurring in young and middle-aged people. Many cases occur in healthy people and may only affect one eye but some are associated with rheumatologic, skin, gastrointestinal, lung and infectious diseases.

What is Intermediate Uveitis?

Intermediate uveitis is commonly seen in young adults. The center of the inflammation often appears in the vitreous (see diagram). It has been linked to several disorders including, sarcoidosis and multiple sclerosis.

What is Posterior Uveitis?

Posterior uveitis is the least common form of uveitis. It primarily occurs in the back of the eye, often involving both the retina and the choroid. It is often called choroditis or chorioretinitis. There are many infectious and non-infectious causes to posterior uveitis.

What is Pan-Uveitis?

Pan-uveitis is a term used when all three major parts of the eye are affected by inflammation. Behcet's disease is one of the most well-known forms of pan-uveitis and it greatly damages the retina.

Intermediate, posterior, and pan-uveitis are the most severe and highly recurrent forms of uveitis. They often cause blindness if left untreated.

Diseases Associated with Uveitis

Uveitis can be associated with many diseases including:

- AIDS

- Ankylosing spondylitis

- Behcet's syndrome

- CMV retinitis

- Herpes zoster infection

- Histoplasmosis

- Kawasaki disease

- Multiple sclerosis

- Psoriasis

- Reactive arthritis

- Rheumatoid arthritis

- Sarcoidosis

- Syphilis

- Toxoplasmosis

- Tuberculosis

- Ulcerative colitis

- Vogt Koyanagi Harada's disease

What are the Symptoms?

Uveitis can affect one or both eyes. Symptoms may develop rapidly and can include:- Blurred vision

- Dark, floating spots in the vision (floaters)

- Eye pain

- Redness of the eye

- Sensitivity to light (photophobia)

Anyone suffering eye pain, severe light sensitivity, and any change in vision should immediately be examined by an ophthalmologist.

The signs and symptoms of uveitis depend on the type of inflammation.

Acute anterior uveitis may occur in one or both eyes and in adults is characterized by eye pain, blurred vision, sensitivity to light, a small pupil, and redness.

Intermediate uveitis causes blurred vision and floaters. Usually it is not associated with pain.

Posterior uveitis can produce vision loss. This type of uveitis can only be detected during an eye examination.

How is uveitis detected?

Diagnosis of uveitis includes a thorough examination and the recording of the patient's complete medical history. Laboratory tests may be done to rule out an infection or an autoimmune disorder.

A central nervous system evaluation will often be performed on patients with a subgroup of intermediate uveitis, called pars planitis, to determine whether they have multiple sclerosis which is often associated with pars planitis.

The eye exams used, include:

An Eye Chart or Visual Acuity Test: This test measures whether a patient's vision has decreased.

A Funduscopic Exam: The pupil is widened (dilated) with eye drops and then a light is shown through with an instrument called an ophthalmoscope to noninvasively inspect the back, inside part of the eye.

Ocular Pressure: An instrument, such a tonometer or a tonopen, measures the pressure inside the eye. Drops that numb the eye may be used for this test.

A Slit Lamp Exam: A slit lamp noninvasively inspects much of the eye. It can inspect the front and back parts of the eye and some lamps may be equipped with a tonometer to measure eye pressure. A dye called fluorescein, which makes blood vessels easier to see, may be added to the eye during the examination. The dye only temporarily stains the eye.

How is Uveitis Treated?

Uveitis treatments primarily try to eliminate inflammation, alleviate pain, prevent further tissue damage, and restore any loss of vision. Treatments depend on the type of uveitis a patient displays. Some, such as using corticosteroid eye drops and injections around the eye or inside the eye, may exclusively target the eye whereas other treatments, such immunosuppressive agents taken by mouth, may be used when the disease is occurring in both eyes, particularly in the back of both eyes.

An eye care professional will usually prescribe steroidal anti-inflammatory medication that can be taken as eye drops, swallowed as a pill, injected around or into the eye, infused into the blood intravenously, or, released into the eye via a capsule that is surgically implanted inside the eye. Long-term steroid use may produce side effects such as stomach ulcers, osteoporosis (bone thinning), diabetes, cataracts, glaucoma, cardiovascular disease, weight gain, fluid retention, and Cushing’s syndrome. Usually other agents are started if it appears that patients need moderate or high doses of oral steroids for more than 3 months.

Other immunosuppressive agents that are commonly used include medications such as methotrexate, mycophenolate, azathioprine, and cyclosporine. These treatments require regular blood tests to monitor for possible side effects. In some cases, biologic response modifiers (BRM), or biologics, such as, adalimumab, infliximab, daclizumab, abatacept, and rituximab are used. These drugs target specific elements of the immune system. Some of these drugs may increase the risk of having cancer.

Anterior Uveitis Treatments

Anterior uveitis may be treated by:

- Taking eye drops that dilate the pupil to prevent muscle spasms in the iris and ciliary body (see diagram).

- Taking eye drops containing steroids, such as prednisone, to reduce inflammation.

Intermediate, Posterior, and Pan-Uveitis Treatments

Intermediate, posterior, and pan-uveitis are often treated with injections around the eye, medications given by mouth, or, in some instances, time-release capsules that are surgically implanted inside the eye. Other immunosuppressive agents may be given. A doctor must make sure a patient is not fighting an infection before proceeding with these therapies.

A recent NEI-funded study, called the Multicenter Uveitis Treatment Trial (MUST), compared the safety and effectiveness of conventional treatment for these forms of uveitis, which suppresses a patient’s entire immune system, with a new local treatment that exclusively suppressed inflammation in the affected eye. Conventionally-treated patients were initially given high doses of prednisone, a corticosteroid medication, for 1 to 4 weeks which were then reduced gradually to low doses whereas locally-treated patients had a capsule that slowly released fluocinolone, another corticosteroid medication, surgically inserted in their affected eyes. Both treatments improved vision to a similar degree, with patients gaining almost one line on an eye chart. Conventional treatment produced few side effects. In contrast, the implant produced more eye problems, such as abnormally high eye pressure, glaucoma, and cataracts. Although both treatments decreased inflammation in the eye, the implant did so faster and to a greater degree. Nevertheless, visual improvements were similar to those of patients given conventional treatment.

Education Navigation

- Monday: 9:00AM - 6:00PM

- Tuesday: 9:00AM - 6:00PM

- Wednesday: 9:00AM - 6:00PM

- Thursday: 9:00AM - 6:00PM

- Friday: 9:00AM - 2:00PM

- Saturday: CLOSED

- Sunday: CLOSED